1. The state of Vue 3 and Composition API

Vue 3 has been released for already a year with its main new feature: a Composition API. As of Autumn 2021, the recommended way to setup a new project is to use Vue 3 with script setup syntax, so hopefully we'll see more and more production-grade apps built on Vue 3.

I had on opportunity to build an app on Vue 3 from scratch, and the information here comes from this experience. This article is meant to show some interesting ways to utilize composition API and how to structure an app around that. The basic knowledge about Vue and Composition API is preferable.

2. Composable functions and code reuse

New composition API unlocks many interesting ways to reuse code across components. A refresher: previously we split component logic according to component Options: data, methods, created, etc:

// Options API style

data: () => ({

refA: 1,

refB: 2,

}),

// Here we often see 500 lines of code ..

computed: {

computedA() {

return this.refA + 10;

},

computedB() {

return this.refA + 10;

},

},With Composition API we are not limited to this structure and can separate code according to features, instead of options:

setup() {

const refA = ref(1);

const computedA = computed(() => refA.value + 10);

/*

Here could be 500 lines of code as well.

But the features can stay near each other!

*/

const computedB = computed(() => refA.value + 10);

const refB = ref(2);

return {

refA,

refB,

computedA,

computedB,

};

},Vue 3.2 introduced <script setup> syntax, which is just a syntactic sugar of setup() function, making the code more terse. From now on, we'll use script setup syntax, as it is the most current one.

<script setup>

import { ref, computed } from 'vue'

const refA = ref(1);

const computedA = computed(() => refA.value + 10);

const refB = ref(2);

const computedB = computed(() => refA.value + 10);

</script>Here's, in my opinion, a big idea. Instead of keeping the features separated using their placement inside script setup, we can split these into their own own files. Here's the same logic done, with splitting up the files:

// Component.vue

<script setup>

import useFeatureA from "./featureA";

import useFeatureB from "./featureB";

const { refA, computedA } = useFeatureA();

const { refB, computedB } = useFeatureB();

</script>

// featureA.js

import { ref, computed } from "vue";

export default function () {

const refA = ref(1);

const computedA = computed(() => refA.value + 10);

return {

refA,

computedA,

};

}

// featureB.js

import { ref, computed } from "vue";

export default function () {

const refB = ref(2);

const computedB = computed(() => refB.value + 10);

return {

refB,

computedB,

};

}

Note that featureA.js and featureB.js export Ref and ComputedRef types, so all this data is reactive!

This specific snippet can seem as a bit overkill, however:

- Imagine the component having 500+ lines of code, instead of 10. With separating logic into

use__.jsfiles, the code gets more readable. - We can freely reuse the composable functions inside the

.jsfiles in multiple components! No more limitations of renderless components with scoped slots or namespace clashing of mixins. Because the composables userefandcomputedstraight from Vue, this code will just work with any.vuecomponent in your project.

Gotcha 1: Lifecycle hooks in setup.

If lifecycle hooks (onMounted, onUpdated, etc.) can be used inside setup, it also means we can use them inside our composable function as well. You can even write something like this:

// Component.vue

<script setup>

import { useStore } from 'vuex';

const store = useStore();

store.dispatch('myAction');

</script>

// store/actions.js

import { onMounted } from 'vue'

// ...

actions: {

myAction() {

onMounted(() => {

console.log('its crazy, but this onMounted will be registered!')

})

}

}

// ...And Vue will register lifecycle hooks even inside vuex! (The question is: should you 🤨🙂)

With this flexibility and power, it's important to understand how and when these hooks are registered. Take a look at the snippet below: Which onUpdated hooks will be registered?

<script setup lang="ts">

import { ref, onUpdated } from "vue";

// This hook will be registered. We call it as normal inside setup

onUpdated(() => {

console.log('✅')

});

class Foo {

constructor() {

this.registerOnMounted();

}

registerOnMounted() {

// It will register as well! It's inside a class method, but it's executed

// syncronously inside setup

onUpdated(() => {

console.log('✅')

});

}

}

new Foo();

// IIFE also works

(function () {

onUpdated(() => {

state.value += "✅";

});

})();

const onClick = () => {

/*

This will not be registered. This hook is inside an another function.

There is no way Vue can reach this method inside setup initialization

The worst thing is that you won't even get a warning, unless the

function is executed! So keep an eye on that.

*/

onUpdated(() => {

console.log('❌')

});

};

// async IIFE will fail as well :(

(async function () {

await Promise.resolve();

onUpdated(() => {

state.value += "❌";

});

})();

</script>Conclusion: declare lifecycle methods in a way that they are executed on setup initialization synchronously. Otherwise, it does not matter where they are declared and in what context.

Gotcha 2: Async functions in setup

We often need to use async/await in our logic. The naive approach is to try this:

<script setup lang="ts">

import { myAsyncFunction } from './myAsyncFunction.js

const data = await myAsyncFunction();

</script>

<template>

Async data: {{ data }}

</template>However, if we try to run this code, the component won't be rendered at all. Why? Because Promises don't track state. We assign a promise to data variable, but it's impossible for Vue to reactively update it's state. Luckily, there are some workarounds:

Solution 1: ref with .then syntax

To render the component we can use .then syntax:

<script setup>

import { ref } from "vue";

import { myAsyncFunction } from './myAsyncFunction.js

const data = ref(null);

myAsyncFunction().then((res) =>

data.value = fetchedData

);

</script>

<template>

Async data: {{ data }}

</template>- At start, we create a reactive ref that equals null

- Async function is called. The script setup context is synchronous, so the component renders

- When myAsyncFunction() promise is resolved, its result is assigned to reactive

dataref and result becomes rendered

Pros: just works

Cons: the syntax is a bit dated, and can get clunky when having multiple .then and .catch chains

Solution 2: IIFE

We can retain the async/await syntax if we wrap this logic inside an async IIFE:

<script setup>

import { ref } from "vue";

import { myAsyncFunction } from './myAsyncFunction.js'

const data = ref(null);

(async function () {

data.value = await myAsyncFunction()

})();

</script>

<template>

Async data: {{ data }}

</template>Pros: async/await syntax

Cons: Arguably looks less clean. An extra ref is still needed

Solution 3: Suspense (experimental)

If we wrap this component with <Suspense> in parent component, we can freely use async/await in setup as in the naive approach!

```jsx

// Parent.vue

<script setup lang="ts">

import { Child } from './Child.vue

</script>

<template>

<Suspense>

<Child />

</Suspense>

</template>

// Child.vue

<script setup lang="ts">

import { myAsyncFunction } from './myAsyncFunction.js

const data = await myAsyncFunction();

</script>

<template>

Async data: {{ data }}

</template>

```Pros: Most concise and intuitive syntax so far

Cons: as of December 2021 this is still an experimental feature and it's syntax is likely to change.

The <Suspense> component has much more possibilities than just async in child component setup. Using it, we can also specify loading and fallback states. I think this is the way forward for creating async components. Nuxt 3 already uses this feature, and for me it will probably be the preferred way, once this feature will be stable

Solution 4: Separate 3-rd party methods, tailored for these cases (see next section)

Pros: Most flexibility

Cons: a package.json dependency

3. VueUse

VueUse library relies on the new functionality Composition API unlocked, giving a variety of helper functions. Same as we wrote useFeatureA and useFeatureB , this library lets you import pre-made utility functions, written in a composable style. Here's a snippet of how it works:

<script setup lang="ts">

import {

useStorage,

useDark

} from "@vueuse/core";

import { ref } from "vue";

/*

An example of localStorage implementation.

This function returns a Ref, so you can edit it rightaway

with .value syntax, without separate getItem/setItem methods.

*/

const localStorageData = useStorage("foo", undefined);

/*

Dark/light helper that detects browser theme.

The returnd value is again basically a ref,

so you can toggle it reactively as well!

*/

const isDark = useDark()

</script>I cannot recommend you this library enough, and in my opinion it's a must-have for any new Vue 3 project:

- Potentially this library can save you many lines of code and lots of your time

- Does not impact bundle size

- The source code is simple and easy to understand. If you find that the library functionality is not enough, you can extend the function. It means you don't risk much, when opting-in to use this library.

Here's how this library addresses the async call execution mentioned previously:

<script setup>

import { useAsyncState } from "@vueuse/core";

import { myAsyncFunction } from './myAsyncFunction.js';

const { state, isReady } = useAsyncState(

// the async function we want to execute

myAsyncFunction,

// Default state:

"Loading...",

// UseAsyncState options:

{

onError: (e) => {

console.error("Error!", e);

state.value = "fallback";

},

}

);

</script>

<template>

useAsyncState: {{ state }}

Is the data ready: {{ isReady }}

</template>This method lets you execute async function right inside setup + gives you fallback option and loading state. Right now, this a preferred method to handle async for me.

Link: useAsyncState doc.

4. If your project uses Typescript

New defineProps and defineEmits syntax

script setup brought a quicker way of typing props and emits in Vue components:

<script setup lang="ts">

import { PropType } from "vue";

interface CustomPropType {

bar: string;

baz: number;

}

// defineProps overloads:

// 1. Syntax similar to Options API

defineProps({

foo: {

type: Object as PropType<CustomPropType>,

required: false,

default: () => ({

bar: "",

baz: 0,

}),

},

});

// 2. Via a generic. Note that PropType is not needed!

defineProps<{ foo: CustomPropType }>();

// 3. Default state can be done this way:

withDefaults(

defineProps<{

foo: CustomPropType;

}>(),

{

foo: () => ({

bar: "",

baz: 0,

}),

}

);

// Emits can also be typed briefer with defineEmits:

defineEmits<{ (foo: "foo"): string }>();

</script>Personally, I will always go for generic style, because it saves us an extra import and is more explicit about null and undefined types, instead of { required: false } in Vue 2 style syntax.

💡 Note that you don't need to manually import defineProps and defineEmits. That is because these are special macroses Vue uses. These are processed in compile-time into "normal" options API syntax. We'll probably see more and more implementation of macroses in future Vue releases.

Typing composable functions

Because typescript requires you to type return of a module by default, in the beginning I wrote TS composables mostly this way:

import { ref, Ref, SetupContext, watch } from "vue";

export default function ({

emit,

}: SetupContext<("change-component" | "close")[]>):

// Is the code below really necessary?:

{

onCloseStructureDetails: () => void;

showTimeSlots: Ref<boolean>;

showStructureDetails: Ref<boolean>;

onSelectSlot: (arg1: onSelectSlotArgs) => void;

onBackButtonClick: () => void;

showMobileStepsLayout: Ref<boolean>;

authStepsComponent: Ref<string>;

isMobile: Ref<boolean>;

selectedTimeSlot: Ref<null | TimeSlot>;

showQuestionarireLink: Ref<boolean>;

} {

const isMobile = useBreakpoints().smaller("md");

const store = useStore();

// and so on, and so on

// ...

}Yet, I think that's a mistake. It's not really necessary to type function return as it can easily be implicitly typed when writing the composable. It can save you plenty of time and lines of code.

import { ref, Ref, SetupContext, watch } from "vue";

export default function ({

emit,

}: SetupContext<("change-component" | "close")[]>) {

const isMobile = useBreakpoints().smaller("md");

const store = useStore();

// The return can be typed implicitly in composables

}💡 In case EsLint marks this as an error, put '@typescript-eslint/explicit-module-boundary-types': 'error', into EsLint config (.eslintrc)

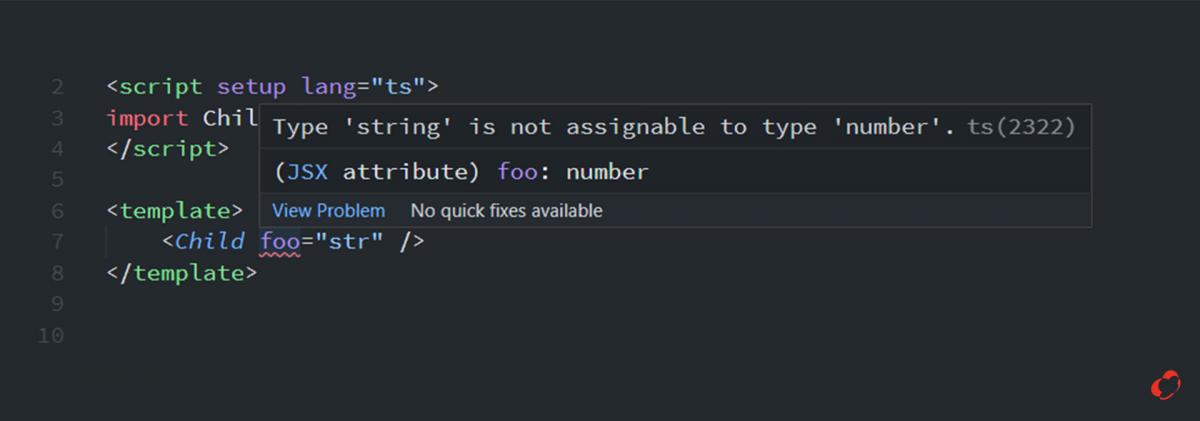

Volar extension

Volar came as a replacement of Vetur as a Vue extension for VsCode and WebStorm. Now it's officially recommended for usage in Vue 3. For me, it's main feature is: typing props and emits out of the box. Which works great, especially if you use Typescript.

Right now, I would always go for Volar in Vue 3 projects. For Vue 2, Volar still works better for me, as less tweaking is needed for it to work.

A useful link: how to register global components in Volar.

5. App Architecture around Composition API

Moving the logic away from the .vue component file

Previously, there were some examples where all logic was done inside script setup . And there were some examples of components that used composable functions imported from outside of a .vue file.

The big code design question is: Should we write all logic outside .vue file? There are pros and cons.

| Write all logic inside setup | Move everything into separate composable functions in dedicated .js/.ts files |

|---|---|

| + No need to write a composable. Easier to make changes | + More extendable project |

| - If you'll need to reuse this code, there will be some refactoring to do | + When writing code, it's easier to concentrate on a single feature. Logic is more separated. |

| - More boilerplate |

What choice I made for myself:

- Use a hybrid approach in small/medium sized projects. Write logic inside setup generally. Put it away into separate js/ts files when the component get too big, or when it's clear that this code will be reused.

- For large projects, just write everything in composables. Use setup solely to handle template namespacing.

Composables usage in open source

Here's an overview of how composables are used in popular open source projects:

Here, it's interesting that composables are separated into private and public types. Private composables are meant to be used internally inside Quasar, while public ones can be accessed by a package user.

Right now, all composables are private (used only internally). However, the project is in early development, and probably this strategy will be more adopted in the future.

Element-plus also uses some composables as well. Here, they are often coupled to specific UI components.

I think, Vue Storefront was one of the earliest adopters of composables, implementing them in Vue 2 (via vue/composition-api). It's interesting that they left these composables as a kind of boilerplate, onto which specific CMS packages can make implementations.